Does this microbiome make me look fat?

By Dawn Harris Sherling, M.D., F.A.C.P.

Carbs or fat? Atkins or South Beach? We spend a lot of time, energy, and money trying to figure out which diet to choose. We agonize over our options and then, a few weeks or months later, we feel guilty when we abandon whatever program we signed up for. But what if I were to tell you that what you think matters very little in terms of your weight. How your bacteria feel about it, on the other hand, probably makes all the difference.

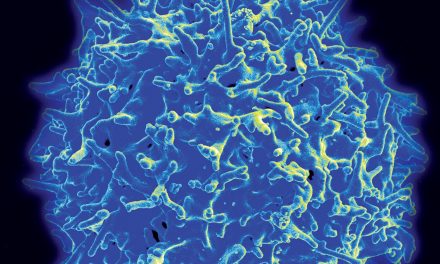

If you haven’t already heard, our intestines (primarily our large intestines) are filled with billions of bacteria contributing more towards the total DNA in our bodies than our actual cells do. This is called the gut microbiome. And our microbiome may be influencing our weight more than anything we choose to do. Our bacteria might be the tiny generals sending out commands to the rest of our body by way of chemical signaling—ordering us to eat more or less and possibly even directing our cells on whether to expend or conserve calories.

Sounds crazy, right? Well, scientists thought so too until 2015, when a study demonstrated that mice fed emulsifiers commonly used in human food (used to make ice cream smooth and baked goods fluffy), were fatter. We can’t digest these emulsifiers and neither can the mice. They pass through to the intestines and are actually used as food by the bacteria in the microbiome. This bacterial food, also called “prebiotics”, causes so-called bad bacteria to grow like, well, to grow like bacteria that you’ve just given a lot of food to. Then, these multiplying bacteria signaled the mice to eat more, perhaps in an effort to further increase their own growth.

But, that’s mice. They are dumb. They listen to bacteria. Humans are higher order beings and we can control ourselves, right? Maybe not. In 2019, scientists took 20 people and housed them in a lab for two weeks. Everything they ate was provided to them and recorded. For two weeks, they were given a diet of unprocessed foods—no emulsifiers or other additives—just fruit, nuts, veggies, meats, whole grains, and other “whole” foods. They could eat as much or as little as they wanted. Then, those same people were fed an ultra-processed diet for two weeks—with the same additives the mice were given plus a few more—basically stuff that comes wrapped in plastic or is available in the freezer section of the supermarket. Those same people ate an average of 500 calories a day more during the ultraprocessed phase of the diet and as a result, gained about 2 pounds in two weeks. Everything else during the study was the same—carbs, fats, protein, sleep, exercise, sodium. The only difference was the food additives in the processed foods. And importantly, most of these additives aren’t food for us, but for our gut bacteria.

Unlike the mice study, the human study didn’t check for the ultraprocessed foods’ effect on the participants’ microbiomes, but many other studies have shown that the emulsifiers and taste enhancers used in processed foods changes the composition of human microbiomes. It isn’t a far leap to consider that what we feed our microbiome, how much and which bacteria we promote by our food choices, wind up determining what signals get sent to our brains and stomachs.

So, what food should we choose? Which diet promotes the most weight loss? Yet another study showed that some people lose a tremendous amount of weight on low carb, while others actually gain weight on the same diet. Likewise, people can lose a ton of weight on a low fat diet, while others gain weight. This holds true for almost every weight loss plan. What works for your friend may not work for you. And this may be due to the fact that although people are remarkably similar, our microbiomes are astoundingly different.

There is some evidence to suggest that we promote the best of our microbiome when we eat real, unprocessed food. Our brains get the signal to eat less and our bodies get the signal to burn more. We may not be what we eat, but our bacteria certainly are. There are a lot of things we could be doing to be healthier, but feeding yourself and your microbiome the foods that nature intended may be a good place to start.